Evaluating the “2% Intersex” Prevalence Figure

Debunking Anne Fausto‐Sterling's Zombie Statistic

Introduction

Please note that this report preserves historical accuracy by using terms related to gender identity and gender ideology, which are topics of intense debate today. However, these terms are included because they appear in past medical literature and discussions.

The claim that around 1.7–2% of people are intersex – roughly “as common as red hair” – often circulates in media and advocacy (GLAAD Media Reference Guide – In Focus: Intersex People | GLAAD). This figure has sparked confusion because it depends on how intersex is defined. Medically, the term Disorders (or Differences) of Sex Development (DSDs) refers to rare congenital conditions where chromosomal, gonadal, or anatomical sex development is atypical ( Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders - PMC ). By that strict definition, the percentage of births considered intersex is far lower than 2%. However, broader definitions used in some academic and activist contexts include a wider array of sex trait variations – leading to a higher prevalence estimate (physiology - Is 1,7% of the population born intersex? - Skeptics Stack Exchange). Further complicating matters, intersex can also describe an identity that individuals may adopt regardless of a formal medical diagnosis. This article critically examines the origin of the “2% intersex” statistic, what conditions are counted (or not) in different definitions, and how these definitions influence public perception. We will break down prevalence estimates for major DSDs using authoritative sources, distinguish medical criteria from broader usage, and discuss intersex as an identity category.

Origins of the “2% Intersex” Figure

The figure of ~1.7% (often rounded to 2%) comes from research by academic Anne Fausto‐Sterling and colleagues around 2000.

An awfully objective quotation from Anne Fausto-Sterling's book *Sexing the Body* (2000) is featured in this caricature of the author.

(GLAAD Media Reference Guide – In Focus: Intersex People | GLAAD) (physiology - Is 1,7% of the population born intersex? - Skeptics Stack Exchange). In a review of medical literature, they tallied all known causes of “nondimorphic” sex development – meaning any departure from the “Platonic ideal” of strictly binary sex chromosomes, gonads, genitalia, and hormones (physiology - Is 1,7% of the population born intersex? - Skeptics Stack Exchange). By adding up the estimated frequencies of a wide range of conditions, they concluded that as many as 1.7% of live births do not conform perfectly to standard male or female development (physiology - Is 1,7% of the population born intersex? - Skeptics Stack Exchange). In Fausto-Sterling’s book Sexing the Body (2000), this was popularized as evidence that intersex traits are not exceedingly rare – “about as common as red hair”, as advocacy groups often phrase it (GLAAD Media Reference Guide – In Focus: Intersex People | GLAAD).

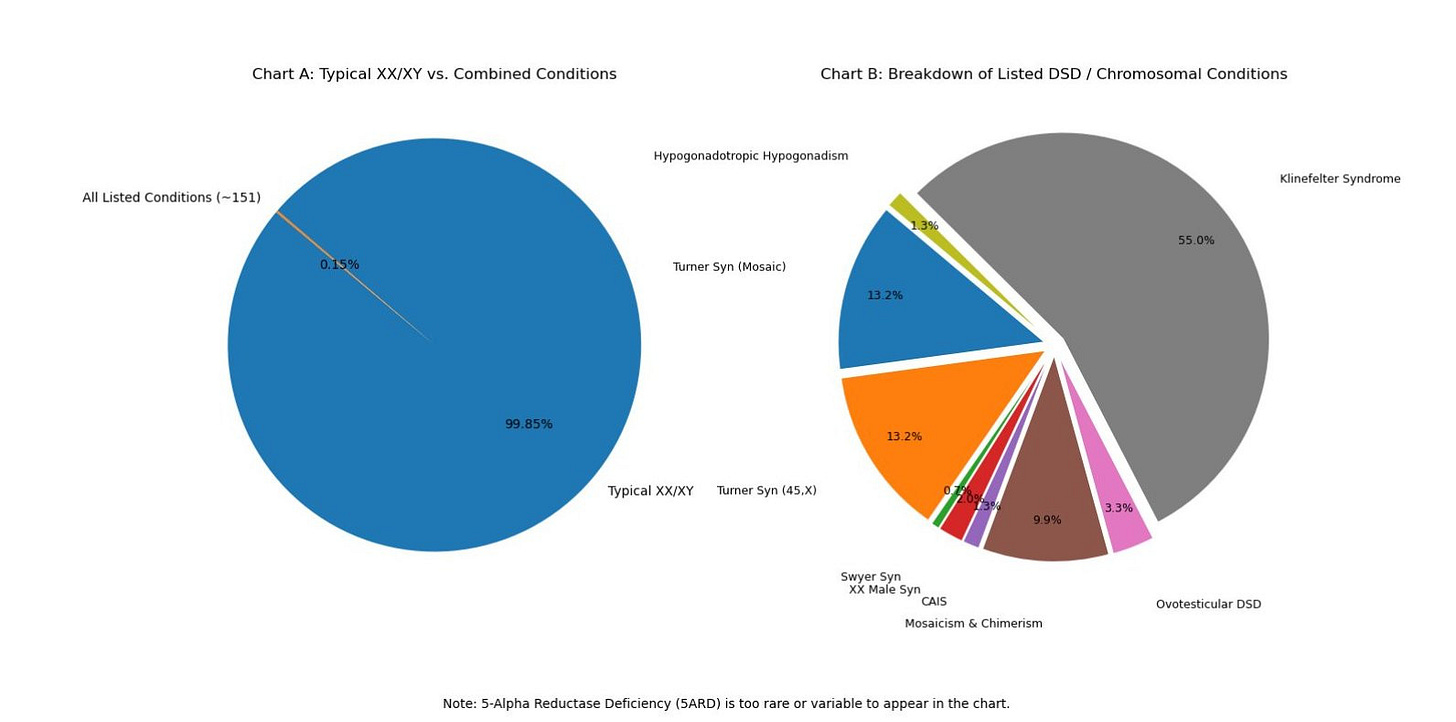

However, this broad 1.7% statistic includes several relatively common conditions that most clinicians would not label as “intersex.” For example, Fausto-Sterling’s tally counted people with Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY males, typically infertile but appearing male) at roughly 1 in 1,000 births, Turner syndrome (45,X females, typically short-statured females with ovarian failure) at about 1 in 2,000 female births, and late-onset (non-classical) congenital adrenal hyperplasia (a mild hormonal variation often not apparent at birth) at about 1 in 66 individuals (How common is intersex? a response to Anne Fausto-Sterling - PubMed) (physiology - Is 1,7% of the population born intersex? - Skeptics Stack Exchange). All these contribute to the 1.7% figure, yet they do not usually result in ambiguous genitalia or mixed sex anatomy at birth. In practice, a baby born noticeably atypical in genital appearance is far rarer than 1.7% – on the order of 0.05–0.07% of births (about 1 in 1,500–2,000) where specialists are called in at birth (How common is intersex? | Intersex Society of North America). Indeed, a 2006 medical consensus estimated that genital anomalies requiring expert evaluation occur in about 1 in 4,500 births ( Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders - PMC ) (≈0.02%).

To understand the 2% claim, it’s important to know what Fausto-Sterling included. Below are examples of conditions counted in the broad definition, and their approximate frequencies:

Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY): ~0.1% of births (around 1 in 500–1,000 male births) (Klinefelter Syndrome: Practice Essentials, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology). Individuals are typically male in appearance, often undiagnosed until adulthood due to infertility or other issues.

Turner syndrome (45,X or mosaic): ~0.05% of births (about 1 in 2,000 female births) (Turner Syndrome: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology). Individuals are female but with missing or partial X chromosome; no ambiguous genitalia.

Late-onset (non-classical) CAH: up to ~1.5% of individuals (Fausto-Sterling used ~1 in 66) (How common is intersex? | Intersex Society of North America). A mild hormone enzyme deficiency that usually causes no genital ambiguity at birth – often presenting later with symptoms like mild virilization or fertility issues.

Mild hypospadias: about 0.1–0.2% of births (forms of hypospadias where the urethral opening on a baby boy’s penis is slightly misplaced) (How common is intersex? | Intersex Society of North America). Minor hypospadias is relatively common and typically corrected surgically; by broad definition any “atypical” genital anatomy counts, though medically this alone isn’t labeled intersex.

Other DSDs: Many genuine DSD conditions were also included, but these are individually much rarer (often 1 in 5,000 to 1 in 100,000 each – see next section). Collectively, however, the sum of their frequencies contributes only a small fraction of that 1.7%. The largest contributors to the 1.7% were actually the relatively high-frequency categories above (especially non-classical CAH) (physiology - Is 1,7% of the population born intersex? - Skeptics Stack Exchange).

Fausto-Sterling’s inclusive approach was meant to challenge the idea of a strict male/female dimorphism by showing a spectrum of natural variation. Another summary of her review stated “deviations from the ideal male or female” could be as high as 2% of live births (physiology - Is 1,7% of the population born intersex? - Skeptics Stack Exchange). These publications essentially broadened “intersex” to mean any innate variation in sex characteristics, however subtle. The Intersex Society of North America (ISNA) echoed this broad usage: “in practice, the term ‘intersex’ is used to refer to anybody who was born with anatomy other than what the Powers That Be define as ‘standard’ male or female.” (physiology - Is 1,7% of the population born intersex? - Skeptics Stack Exchange). That broad umbrella covers a wide range of traits – from chromosome patterns like XXY or X0, to hormonal differences, to ambiguous genitalia.

Not everyone agreed with lumping all these cases together. In 2002, physician Leonard Sax argued that Fausto-Sterling’s 1.7% statistic was misleadingly high because it included conditions not usually considered intersex by medical experts (How common is intersex? a response to Anne Fausto-Sterling - PubMed) (physiology - Is 1,7% of the population born intersex? - Skeptics Stack Exchange). Sax proposed reserving “intersex” for conditions where chromosomal sex doesn’t match the external sex phenotype, or where the phenotype cannot be classified as male or female (How common is intersex? a response to Anne Fausto-Sterling - PubMed). This narrower definition would exclude syndromes like Klinefelter and Turner (because those individuals are unambiguously male or female, albeit with atypical chromosomal makeup) and exclude late-onset CAH (since it doesn’t affect birth sex traits) (How common is intersex? a response to Anne Fausto-Sterling - PubMed). Using the stricter criteria, Sax calculated the “true” prevalence of intersex to be only about 0.018% of the population (How common is intersex? a response to Anne Fausto-Sterling - PubMed) (physiology - Is 1,7% of the population born intersex? - Skeptics Stack Exchange). That is roughly 1 in 5,500 – almost 100 times lower than the 1.7% figure. In other words, if one only counts the classic DSD cases involving clear mix-ups between chromosomal, gonadal, or anatomical sex, the number of intersex births is on the order of a few thousandths of a percent. The gulf between ~0.02% and ~2% highlights how different definitions dramatically change the statistics (physiology - Is 1,7% of the population born intersex? - Skeptics Stack Exchange).

To summarize, the commonly cited 1.7–2% figure originates from an expansive definition put forward by Fausto-Sterling (2000) (physiology - Is 1,7% of the population born intersex? - Skeptics Stack Exchange). It included not only medically recognized intersex/DSD conditions, but also more prevalent sex chromosome anomalies and late-onset hormone conditions. More conservative definitions confined to “medically diagnosable DSDs” yield prevalence estimates closer to 0.02–0.05%. This divergence is at the heart of debates over intersex statistics.

Medically Defined DSDs and Their Prevalence

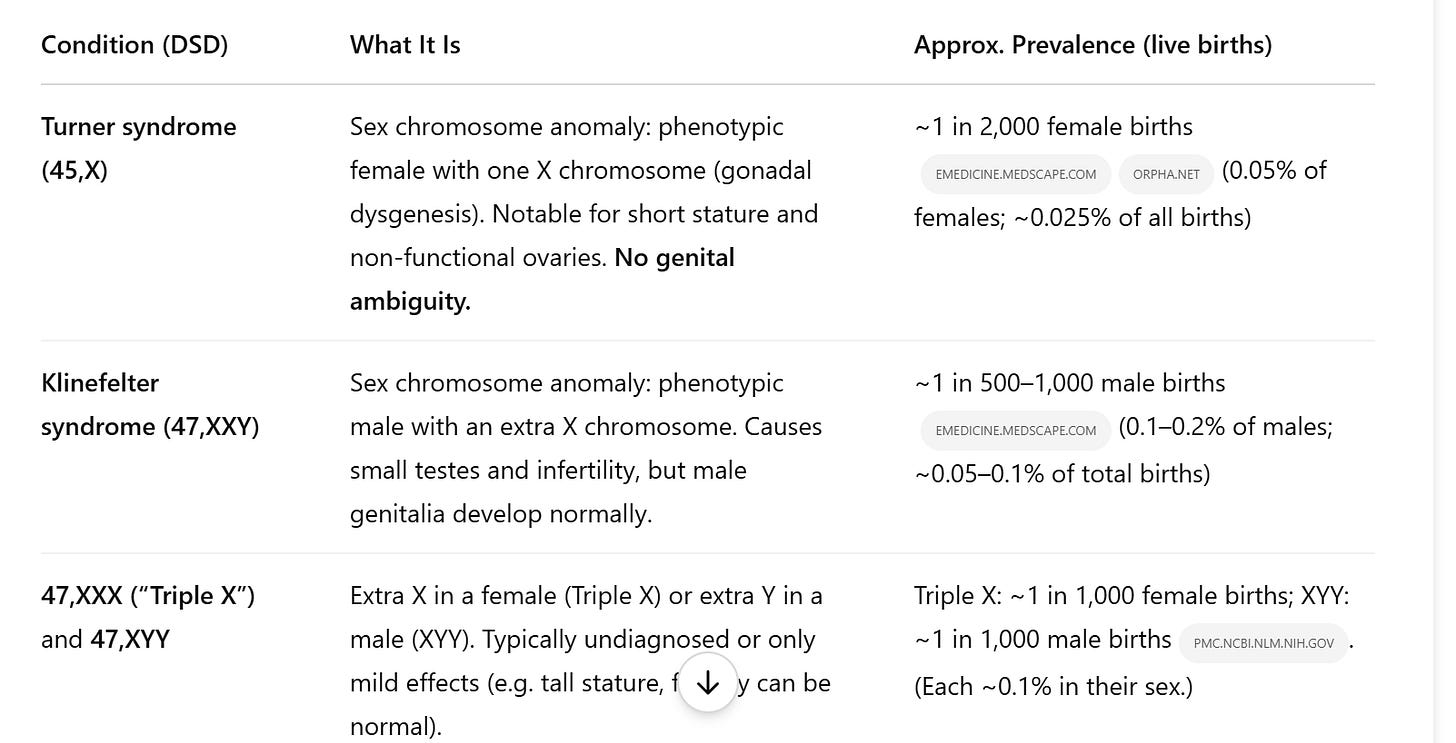

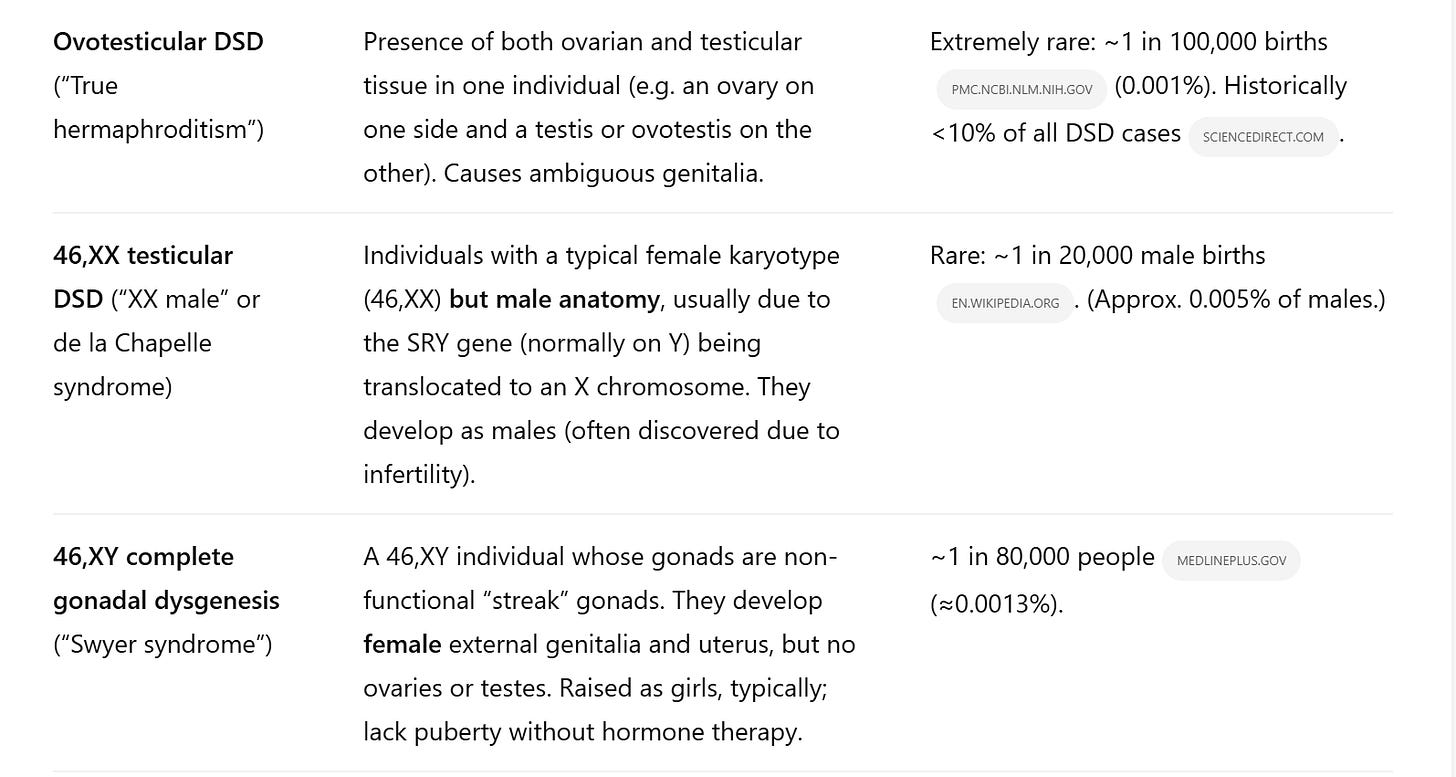

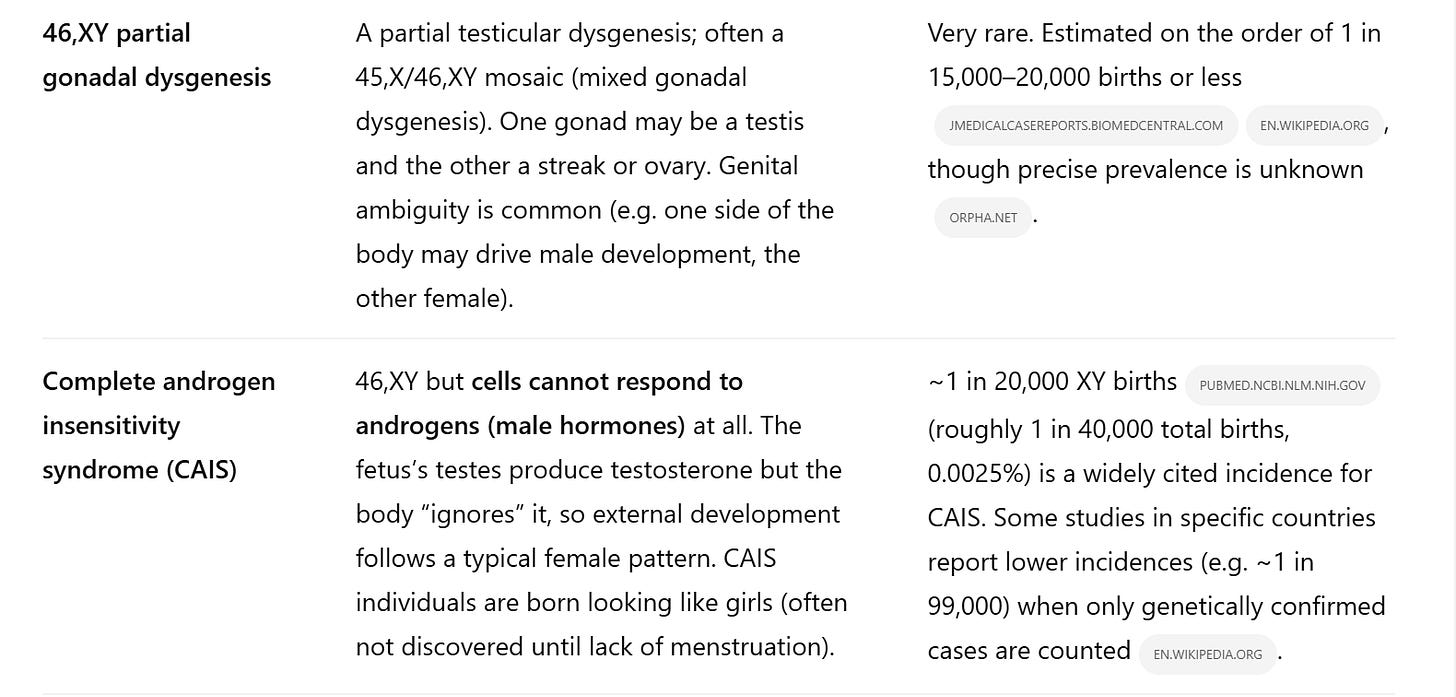

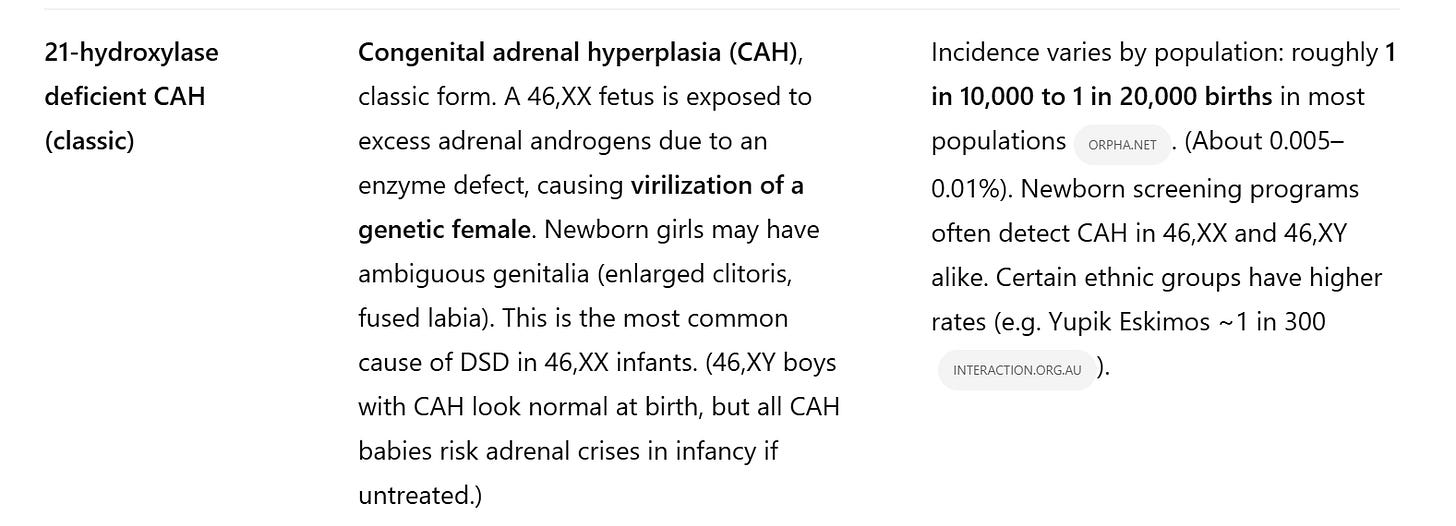

Clinicians today often use the term Disorders of Sex Development (DSDs) to describe congenital conditions involving atypical development of chromosomal, gonadal, or anatomical sex ( Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders - PMC ). (Many advocate the term “Differences of Sex Development” as a less stigmatizing alternative, but the abbreviation DSD is the same.) These diagnoses are typically made when an infant is born with ambiguous genitalia, or when puberty and fertility patterns reveal an underlying sex-development variation. Below is a breakdown of major DSD conditions and best-estimate frequencies from medical literature:

Table: Prevalence of selected congenital DSDs based on medical sources. (Note: Frequencies are approximate and can vary by population. “Births” refers to live births of either sex unless otherwise specified.)

As the table shows, each individual DSD condition is quite rare – many on the order of one per tens of thousands or fewer. Even the most “common” intersex-related conditions (Turner or Klinefelter syndromes, and mild CAH in certain groups) are on the order of 0.1% or less. If one were to only count those DSDs that typically produce ambiguous sex characteristics at birth (for example, CAH in XX infants, AIS, severe hypospadias, gonadal dysgenesis, ovotestes, etc.), the total frequency is a small fraction of 1%. A frequently cited medical estimate is that around 1 in 1,500 to 1 in 2,000 births (0.05–0.07%) have genital anatomy so atypical that specialists are consulted (How common is intersex? | Intersex Society of North America). This aligns with the stricter prevalence (~0.02–0.05%) noted earlier. In short, using medical diagnostic criteria, intersex/DSD conditions are uncommon to rare. They are certainly not “2% of the population” by these definitions.

It’s worth noting that Klinefelter and Turner syndromes are often included under DSD classification (they involve sex chromosome abnormalities), but doctors historically did not call them “intersex” because those individuals are not sex-ambiguous – they are clearly male or female, albeit with developmental differences (like infertility or lack of puberty). The 2006 consensus that introduced the DSD terminology in fact lists sex chromosome aneuploidies as part of the DSD spectrum ( Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders - PMC ) ( Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders - PMC ). So medically, someone with XXY or X0 has a “difference of sex development,” but in practice they might not know it unless tested, and they usually are raised without question of their assigned sex. This ambiguity in inclusion partially explains why some counts vary: some statistics for “intersex” include XXY/X0, others do not.

In the medical context, disorders of sex development are defined by objective criteria – for example, a mismatch between chromosomal sex and phenotypic sex, or ambiguous reproductive anatomy. The focus is on congenital conditions identifiable through clinical observation or genetic/hormonal testing. These conditions have known (if sometimes imprecise) incidence rates, as listed above. Authoritative sources like Orphanet, specialist textbooks, or large population studies provide the prevalence figures cited, grounding them in epidemiological research rather than advocacy.

Broader Definitions and Activist Perspectives

Outside the clinical realm, the term “intersex” is often used more broadly to encompass any natural variation in sex characteristics that deviates from cultural ideals of a binary male/female body. This includes conditions that may not be considered DSDs in a strict sense, such as those that do not cause visible ambiguity in genital or reproductive anatomy.

For example, intersex activists commonly include people with sex chromosome variations (like XXY, X0, XXX, XYY) in the intersex umbrella, as well as those with subtler hormonal variations. The rationale is that these are “innate variations of sex characteristics” – a phrase often used in human rights contexts – and that such traits challenge the idea of a strict sexual binary. An Australian advocacy organization defines people with intersex variations as those born with “any innate variation of sex characteristics” – not only genitals, but also chromosomes, gonads, hormone function, etc., that differ from the norm ( Population figures – InterAction) (physiology - Is 1,7% of the population born intersex? - Skeptics Stack Exchange). By this broad definition, someone with Klinefelter syndrome or Turner syndrome is an intersex person, even though they might not have realized it at birth. Similarly, a girl with late-onset CAH – who may develop signs of elevated androgens (like excess body hair or irregular periods) in adolescence – could be considered as having an intersex trait, though clinically she wouldn’t have been labeled intersex in infancy.

Hormone-related variations that are not included in the medical DSD list can greatly expand prevalence numbers. A prime example is the “non-classical” CAH mentioned earlier. Non-classical CAH is fairly common in certain ethnic groups (e.g. as many as ~3.7% of Ashkenazi Jews carry it) ( Population figures – InterAction), and on the order of 1 in 200 to 1 in 1,000 in many populations – which is orders of magnitude more frequent than classic CAH at birth. Fausto-Sterling’s analysis assumed roughly 1.5% of people have some form of late-onset adrenal hyperplasia (How common is intersex? | Intersex Society of North America), thus contributing the bulk of the 1.7%. Most endocrinologists would not classify those individuals as “disorders of sex development” because they typically have normal genital anatomy corresponding to their chromosomes (the effects are more metabolic or post-puberty). But under a broader “sex variance” lens, they do count, since their sex hormone profile is atypical and it can affect secondary sex characteristics.

Another category is anatomical variations that don’t impair gender assignment but differ from the norm: for instance, hypospadias (a minor to moderate malformation of the penis in newborn males). Hypospadias occurs in up to ~0.3–0.5% of male births (especially the milder forms) (How common is intersex? | Intersex Society of North America). Typically, a boy with hypospadias is still recognizably a boy (this condition is usually corrected surgically and the child is raised male). Most medical professionals do not consider isolated hypospadias to make someone “intersex.” Yet some intersex umbrella definitions might include severe hypospadias (where the urethral opening is very far from the tip, or accompanied by undescended testes) as part of intersex, since in those cases sex differentiation in utero was atypical. Indeed, severe hypospadias can be a symptom of conditions like partial androgen insensitivity or mixed gonadal dysgenesis – which are DSDs. The line can blur between a standalone minor anomaly and an intersex condition, and different sources count them differently. The ISNA/Blackless data, for example, listed hypospadias in their frequency breakdown and included even the mild cases in the tally (How common is intersex? | Intersex Society of North America).

The activist and human-rights framing of intersex tends to emphasize inclusivity and self-identification. It often uses a social definition such as “born with sex characteristics that don’t fit typical definitions of male or female.” This can incorporate internal traits (like possessing a uterus in an XY person or an unusual gonadal makeup) that might never be obvious externally. It also deliberately distances from the term “disorder,” preferring to speak of variations. The GLAAD Media Guide, for instance, defines intersex as having “one or more innate sex characteristics… that fall outside of traditional conceptions of male or female bodies” (GLAAD Media Reference Guide – In Focus: Intersex People | GLAAD). By that definition, a large variety of conditions qualify – essentially, all the conditions in the medical DSD table, plus additional ones (like Klinefelter, Turner, and mild CAH) which medicine might categorize separately. This broad approach yields the “as high as 1.7%” prevalence that GLAAD and others cite (GLAAD Media Reference Guide – In Focus: Intersex People | GLAAD).

It’s important to clarify what the 1.7% does not mean: it does not mean 1.7% of people are born with genitals so ambiguous that their sex is unclear. As shown, those cases are far rarer (well under 0.1%). The ~2% figure mostly reflects the inclusion of less obvious variations. For public perception, however, this nuance is often lost. When people hear “nearly 2% of humans are intersex,” they might imagine one in every 50 babies is born visibly between sexes, which is not true. The broad definition proponents would respond that biological sex isn’t only about genitals – it’s chromosomes, hormones, internal organs, etc., and many more than 0.1% of people have one of those aspects outside the typical binary range. For example, a woman with XY chromosomes and androgen insensitivity has an intersex trait even if externally she looks typical female; a man with XXY chromosomes has an intersex trait even if he looks typical male. Underlying this debate is a question of which variations “count” as intersex. Activist definitions cast a wide net to foster community and visibility for all those with atypical sex traits, even if many in that group don’t face the same social or medical challenges as someone with, say, ambiguous genitalia at birth.

Critically, different definitions can shape public understanding. A broader definition can highlight the prevalence of natural sex diversity, countering the misconception that intersex conditions are nearly mythical. It has been effectively used to advocate that intersex people are “not so rare” and thus deserve attention in law and medicine. On the other hand, medical professionals caution that conflating very different conditions under one label may be confusing. For instance, someone with Klinefelter syndrome often doesn’t learn of it until adulthood (if ever), and may not view it as a core part of their identity, whereas someone with a more immediately apparent DSD might have intensive medical interventions and social issues from infancy. The needs and experiences across that spectrum can differ greatly.

Academic viewpoints also vary. In sociology and gender studies, scholars sometimes adopt the broad definition to discuss how society constructs a sex binary despite this spectrum of traits. They may cite the ~2% figure to challenge strict binary classification in sports or legal documents, for example. Other academics, particularly in medicine or biology, stick to narrower definitions to maintain diagnostic precision. Some recent genetics papers note that if one sequences genomes widely, the proportion of people with some intersex-related genetic variation could be a fraction of a percent – but many of those individuals never manifest any intersex phenotype ( Population figures – InterAction). Thus, even academically, context matters: a biology paper might frame intersex in terms of identifiable developmental disorders, whereas a human rights paper might frame it in terms of populations with any sex trait variance.

In summary, broad definitions of “intersex” count many more people – including those with only subtle or internal differences – and thereby yield a higher prevalence (on the order of 1–2%). Narrow definitions count only the classic DSD cases with evident sex ambiguity or inconsistency, yielding a much smaller prevalence (~0.02–0.05%). Neither is “right” or “wrong” per se; they are used for different purposes. But it is crucial to specify the scope when citing statistics to avoid misleading impressions.

Intersex as an Identity Category

Beyond medical diagnosis and biological traits, “intersex” can also be an identity – one that an individual may embrace as part of their personal or social experience. Not everyone with an intersex trait knows about it or identifies with the intersex community. Conversely, some people might self-identify as intersex even in the absence of a confirmed medical condition, especially if they feel their sex characteristics or experiences don’t align with typical male or female norms.

Historically, many patients with DSDs were not told their diagnoses (“clinical non-disclosure”) ( Population figures – InterAction), so they might not have had the opportunity to identify as intersex. But in recent decades, there has been a growing intersex advocacy movement. People born with various DSDs have formed organizations, chosen “intersex” as a unifying label, and advocated against shame and secrecy. This means that intersex is not only a medical descriptor but also a social identity and a minority group. For example, an individual with Complete AIS who was raised female might discover her condition in adolescence and later join intersex advocacy – identifying openly as intersex (not just as a woman with CAIS). Another person with XXY (Klinefelter) might or might not consider himself intersex; it often depends on personal affinity with the intersex community or awareness of the concept.

Interestingly, recent population surveys have tried to measure how many people knowingly identify as intersex or having a variation of sex characteristics. In Australia, a first-of-its-kind national survey in 2021–2022 asked adults if they were born with a variation of sex characteristics (intersex/DSD). About 0.3% of Australian adults answered “yes” to knowing they have such a trait ( Population figures – InterAction). In New Zealand’s 2023 census, about 0.4% of adults responded that they have an intersex variation ( Population figures – InterAction). These percentages are smaller than the oft-cited 1.7%, which makes sense – many in that 1.7% may not even be aware of their condition (for instance, someone with mild late-onset CAH or a mild chromosome mosaic might never be diagnosed, or might just check “no” or “don’t know” on a survey). Notably, in the Australian data an additional 0.7% responded “don’t know” when asked if they have a variation ( Population figures – InterAction), which hints that a portion of the population might unknowingly have intersex traits or were unsure of the question. These surveys, while preliminary, show that the visible/interacting intersex population (people who know and possibly identify as such) is a subset of the broader group defined by biological incidence.

Identity adoption can also be influenced by personal and cultural factors. Some individuals with intersex traits may prioritize a specific diagnosis identity (e.g., “I have CAIS” or “I have Klinefelter syndrome”) and not use the term intersex for themselves, especially if they have a strong male or female gender identity and don’t feel “between sexes.” Others embrace “intersex” as a way to build community and advocate for rights, including the right to bodily autonomy (for example, intersex groups often campaign against non-consensual surgeries on infants). There are also cases where people who felt very atypical in terms of gender or body might call themselves intersex without a known DSD, though this is less common and sometimes conflated with transgender (which is different: intersex is about biology, transgender about gender identity). Activists take care to distinguish: “Do not confuse having an intersex trait with being transgender,” as GLAAD notes (GLAAD Media Reference Guide – In Focus: Intersex People | GLAAD). Most intersex people are assigned a binary sex at birth (male or female) and will keep that identity – intersex is about the traits they were born with, not about changing gender. However, a higher proportion of people with certain DSDs do experience gender identity shifts or fluidity compared to the general population. For example, some individuals with partial androgen insensitivity or 5-ARD who were raised female later transitioned to live as male when they matured, because their bodies masculinized further at puberty or they felt male-typed (GLAAD Media Reference Guide – In Focus: Intersex People | GLAAD). Conversely, some raised male may transition to female. These outcomes are part of why the intersex community intersects (no pun intended) with LGBT topics, but it’s a distinct phenomenon.

Public perception of intersex people is evolving as more intersex individuals share their stories and as legal recognition improves. Intersex is now recognized as a protected characteristic in some anti-discrimination laws. On the social identity front, intersex people often refer to non-intersex people as “endosex” (meaning having endo-, or typical, sex characteristics). This mirrors how the term “cisgender” is used as a counterpart to transgender – “endosex” is a counterpart to intersex. It underscores that being intersex is a distinct experience, not just a medical condition.

When considering prevalence, the identity-based prevalence (how many openly identify or know they are intersex) will be lower than the biological prevalence (how many actually have a trait), due to underdiagnosis, secrecy, or personal choice. The gap between 0.3–0.4% survey findings and the theoretical ~1-2% suggests many people with intersex variations may not know or may not publicly identify as such. Over time, if awareness and openness increase, the identity-prevalence might rise. For now, these numbers give a rough sense: only a few in a thousand people will check “yes, I have an intersex trait” on a survey ( Population figures – InterAction) ( Population figures – InterAction), but the true number who do have intersex traits could be a couple in a hundred (if one includes even the subtle cases).

Conclusion

The “2% of the population is intersex” figure is accurate only under an expansive definition that includes a wide range of sex-chromosome, hormonal, and anatomical variations. This figure’s origin lies in academic attempts to illustrate the natural diversity of sex development (physiology - Is 1,7% of the population born intersex? - Skeptics Stack Exchange). Under a narrow medical definition, focusing on diagnosable DSD conditions that cause evident sex-characteristic discrepancies, the prevalence of intersex conditions is much smaller – on the order of a few per ten thousand births (How common is intersex? a response to Anne Fausto-Sterling - PubMed) (physiology - Is 1,7% of the population born intersex? - Skeptics Stack Exchange). Both perspectives have validity in their contexts: the broad view reminds us that human biology doesn’t always fit neat binary categories (hence a few percent of people have some intersex trait), while the narrow view is crucial for clinical care and accuracy (only a very small fraction of babies require sex assignment scrutiny or special medical intervention at birth).

Understanding these distinctions helps avoid confusion. When we hear statistics about intersex prevalence, we should ask: Which definition is being used? A study of “DSDs” in a medical journal may report a far lower incidence than an advocacy website talking about “intersex people” – because they are effectively talking about different groups, even though there is significant overlap. Likewise, when considering intersex as a social identity, it’s important to recognize that not everyone with an intersex trait knows about it or embraces the label, so social statistics will differ from biological ones.

In evaluating the 2% figure, it’s clear that definitions matter immensely. Medical, activist, and academic communities may use the same word “intersex” in slightly different ways. This has tangible consequences: for instance, broad definitions can impact public policy arguments (such as calls to include intersex in sex education or to reconsider binary sex categories in sports), whereas narrow definitions might influence clinical protocols (such as how frequently doctors encounter intersex newborns and how to manage care). It can also impact public perception – a broad definition might foster greater acceptance by showing intersex is “not so rare,” while a narrow one might focus attention on the specific health needs of the rare conditions.

Ultimately, being clear about criteria is a form of respect both to facts and to people’s lived realities. If one claims “2% of people are intersex,” it should be explained that this includes many who will never even know it, rather than implying 1 in 50 people has ambiguous genitals. Conversely, if one claims “intersex is extremely rare,” it should be clarified that visible or medically recognized cases are rare, but many more have subtler intersex traits. By appreciating these nuances, we gain a more accurate and empathetic understanding of intersex prevalence – recognizing both the biological diversity and the human experiences behind the statistics.

Sources: Blackless et al. (2000) (physiology - Is 1,7% of the population born intersex? - Skeptics Stack Exchange); Sax (2002) (physiology - Is 1,7% of the population born intersex? - Skeptics Stack Exchange); ISNA frequency data (How common is intersex? | Intersex Society of North America) (How common is intersex? | Intersex Society of North America); Hughes et al. (2006) ( Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders - PMC ); MedlinePlus, Orphanet, and NIH resources on specific conditions (Turner Syndrome: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology) (Klinefelter Syndrome: Practice Essentials, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology) (Complete Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome - PubMed) (Swyer syndrome: MedlinePlus Genetics) ( Testicular differentiation in 46,XX DSD: an overview of genetic causes - PMC ); Australian ABS 2024 report ( Population figures – InterAction); GLAAD & interACT guidelines (GLAAD Media Reference Guide – In Focus: Intersex People | GLAAD). Each of these sources and studies uses slightly different scopes to discuss intersex prevalence, underscoring the importance of context when evaluating the “2%” figure.

Funny how prior to the takeover & relabelling of *HBIGDA into WPATH circa 2007 & the repugnance towards Harry Benjamin for being too bigoted for failing to acknowledge gender expressions outside of the gender binary (as per *the Yogyakarta Principles), but when it’s advantageous/convenient, they/them selectively ‘reach back’ to bolster their citation numbers —like a typical “con-man” would.

The Svengali requires numerous moving parts to compensate for all the ‘run-with-premise’, so maybe use the no good awful pre-Yogyakarta Principle era materials & literature?! 🤔